Selectivity, Bazball, and Kohli

Test batters have to be choosers, but what are the best choices and who choose well?

Test cricket batting is about decisions. Runs don’t come easily, but you still have to choose the right deliveries to attack. It’s like getting stuck on an uninhabited island. You’re starving but still have to be cautious of not ending up poisoning yourself. Those who find the safe deliveries early and stick to them tend to survive. The aim of this piece is to see how much a batter is able to stick to the selection of the target line-length for boundaries and if it means anything for batting averages.

Selection Strength

(Attack is true for deliveries where runs off the bat ≥ 2, considering only controlled shots)

We need to see the extent to which a batter’s attacking distribution is skewed towards a few line-length pairs in an innings. Gini coefficients help here. These values vary from 0 (uniform attack distribution over all line-lengths faced by the batter) to 1 (all attacking shots on one line-length). It is also important to note here that we are not concerned with a batter’s attack percentage. We just want the specificity—something which is taken care of because Gini cares about distribution, not scale. So a boundary distribution of, let’s say, 1, 2, 1 on three line-length pairs will have the same value as a distribution of 2, 4, 2. These values are calculated for all innings of a batter, the average of which is the average selection strength.

High Selection Strength Batters and Pace - Spin Trends

(year>=2016 is considered for this analysis)

Lets start with spin. Who’ve been the best in selection strength against spin?

Sarfaraz, Williamson, Latham, Pant, and Rahim are names widely accepted to be efficient against spin. There’s also a clear domination of Asian batters here (7). Good batters of spin have good selection strength. The most common pair has been good length outside off, which is quite expected. Travis Head, though, has cashed in the most on full deliveries. For Pant, outside off good length has accounted for 38.2 percent of all his attacking shots against spin—the most.

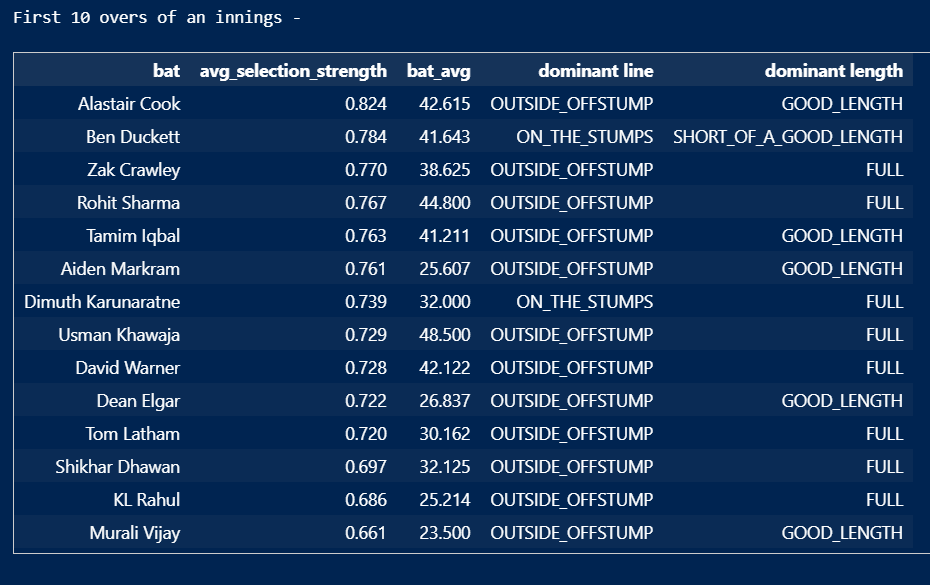

Against pace -

The correlation of selection strength with batting averages is weaker for pace (0.4) compared to spin (0.52). This is probably because a pacer’s line-length spread is more noisy, and there might be more loose options to cash in on compared to a spinner. Just like it was with Asian batters against spinners, here we see 6 SENA men in the top 10. Another point in favour of selection strength.

Unlike spin, the pairs attacked against pace have varied in different conditions. Full length has been punished more in SENA and good length more in Asia (line - outside off). And this shows in the selection strength as well. Putting a filter for SENA nations against pace gets batters like Markram and Babar in the top 10—who are known to play the cover drive well.

When bowlers are good, selectivity is more. Among the 20 most experienced pacers (since 2016), as many as 8 bowlers in the top 10 (in terms of selection strength batters have played with against them) had a better average than the mean of 28.45. Bumrah’s selection strength of 0.844 would have got him 8th place in this list. The spinners' top 20 list had 6 better-than-mean bowlers in the top 10.

Selection Strength and Bazball

The formula of test match scoring is going more towards “better start attacking before you get out.” Bazball fit pretty well with this formula. And what England batters have done well in this is choosing the right lines and lengths. The selection strength has gone from 0.74 pre-Bazball (from 2016 to before Stokes’ captaincy) to 0.79. In England, more than half (52%) of English batters were most dominant on the good length before Bazball. The focus has now shifted to short of good length.

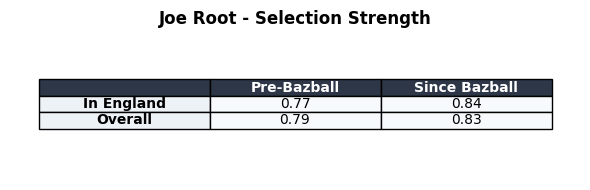

Joe Root specifically—who has the best selection strength among English batters right now—has blended pretty well in this new approach. He has upgraded both his average and strike rate. In England, the upgrade in his stats has been even better.

Virat Kohli: A case of sub-optimal selectivity

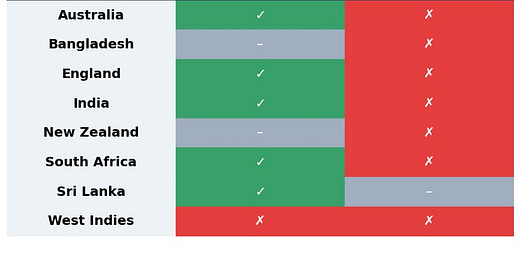

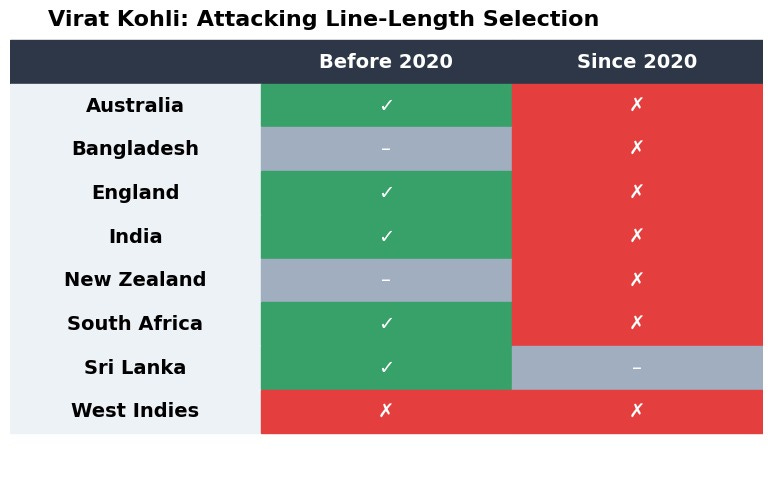

Kohli has probably seen the two most contrasting halves any batter has ever gone through in Tests. Interestingly, his selection strength has increased from 0.71 to 0.79 from pre-2020 to after. His dominant length has gone from good to full. But what Kohli failed to identify in the past few years are the optimal line-lengths to attack against pace. This graphic shows where Kohli’s dominant line-length pair matched with the optimal pair of the country—and where they didn’t. The change from all greens to all reds is striking.

It is easy to observe that Kohli has been guilty of committing to wide outside off post-2019. In England, for example, Kohli attacked wide outside off, full deliveries the most—where the optimal pair was outside off, short of good length. In New Zealand, it was the same "going wide" issue. Before 2020, it was only the West Indies (the only red) where he did that. The key thus is not only to be selective, but also to select well.

Liked what you read? Consider subscribing!